Over the last century, archaeologists have uncovered many treaties from the Ancient Near East (ANE) that served to regulate the affairs between powerful nations and their vassal states. Scholars have subsequently shown that many biblical texts follow the format of these vassal treaties, especially the covenant rituals found in portions of Joshua and Deuteronomy. Frank Moore Cross tells us, “The parade example of the covenant ritual is found in the accounts of Joshua's covenant making in Joshua 24:2-28 happily supplemented by Joshua 8:30-34 and Deuteronomy 27 (11) 15-26.”[1]

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

The Fall Festival in Jacob 2-3

Some weeks ago I started a series of posts that attempted to identify a number of Book of Mormon texts that appeared to have the autumn or fall festival (Day of Atonement/Feast of Tabernacles) as their setting. In one of the first posts in this series (“The Annual Fall Festival in the Book of Mormon”), I documented a few reasons why the three festivals in the harvest month of Tishri (Num 29; Lev 23) were originally part of a single fall harvest festival that contained elements of what would later be separated into the separate feasts. I noted that some of the themes from this festival appeared in the form of imagery of gates and robes used by Book of Mormon prophets. In “A Tower and a Name: Benjamin as the Anti-Nimrod” I made the case that the theology of this fall festival explains the context behind the tower story in Genesis and that King Benjamin is consciously using these same festival themes as well as the tower rebellion as a reference point in his narrative to address descendants of the those who came from that tower. For the reasons given below, I also believe that this fall festival underlies the sermon in Jacob 2-3 and that this context gives Jacob's words added depth.

Labels:

atonement,

Fall Festival,

Jacob

Monday, July 5, 2010

Gates and the Divine Council in the Book of Mormon

Open to me the gates of righteousness: I will go into them, and I will praise the LORD. (Psalm 118:19)

Cosmology in the ancient near east represented both the underworld and the heavens as being barred by a series of portals or gates guarded by angels placed there by divine commission to keep out the unworthy. Mortals desiring entrance to these worlds were required to traverse the doors and bypass the keepers of the portals. The earthly application of this principle resulted in special offices of priests acting as keepers of the sacred gates of the temple asking questions about the purity of those who would enter: “Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord?” (Ps 24:3; see also Ps 15 and 95). We see this gate-salvation imagery used by the Savior in the New Testament: “Enter ye in at the strait gate . . . Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it” (Mat 7:13-14 KJV; see also Luke 13:24). The metaphor is also used frequently in the Book of Mormon: “Yea, thus we see that the gate of heaven is open unto all, even to those who will believe on the name of Jesus Christ” (Hel 3:28; see also 2 Ne 4:32; 31:9, 17, 18; 33:9; Jac 6:11; 3 Ne 11:39-40; 14:13-14; 18:13; 27:33). However, in a departure from the usual idea of priests and angels as keepers of the threshold, Jacob in his great sermon on the atonement (2 Ne 6-10) refers to God himself standing at the gate. This metaphor echoes old ideas about the divine council sitting in judgment on the Day of Atonement and reflects strains of similar thought in the Bible and other ancient near eastern texts.

Labels:

divine council,

gates,

Jacob

Sunday, June 27, 2010

Shades of Enoch: Steadfast in Keeping the Commandments

There are a number of Book of Mormon passages that appear to converge with themes from Enochian literature. One of these occurs when Lehi pleads with his sons Laman and Lemuel to be as consistent and steadfast as certain elements in nature:

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

A Tower and a Name: Benjamin as the Anti-Nimrod

The name of the LORD is a strong tower. (Prov. 18:10)

In a veiled story in Genesis associated with a Babylonian kingship rite, Nimrod builds a temple-tower to “make a name” for his people, the result of which is a confusion of tongues and scattering of the people. In the Book of Mormon, King Benjamin builds a tower at the temple in Zarahemla in order to give his people a name and pronounce his son a king. And he does this after the Nephites have discovered a remnant of scattered Israel who has experienced a degeneration of tongues and who has mixed with the seed of those who left Nimrod's temple-tower. In doing so, Benjamin seems to be deliberately constructing an event that is both related and opposed to what happened on the plains of Shinar. And both episodes seem to be connected to the yearly fall festival in ancient Israel.

Labels:

Alma,

Babel,

Benjamin,

Day of Atonement,

Fall Festival,

Jacob,

name,

Nimrod,

temple,

tower

Monday, June 7, 2010

“Rid of Your Blood”: Robes and Atonement in the Book of Mormon

Mankind has always been preoccupied with sin and death. In the temple-centric world of ancient Israel, the effects of sin resulted in rupturing the original covenant of creation, allowing chaos to disorder the universe until these bonds could be renewed on the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16), when the Lord would redeem his people by atoning for their sins. As I noted in an earlier post, The Annual Fall Festival in the Book of Mormon, the Day of Atonement was part of the larger fall enthronement festival that saw the Lord celebrated as king and victor over the monsters Rahab and Leviathan and represented the final day of judgment, when the forces of evil would be bound, the prisoners would go free, and the people and their land would be healed. On this one day every year, the High Priest would set aside his usual ornate clothing to don simple white linen robes of purity, entering beyond the veil of the temple into the Holy of Holies with a bowl that carried the fresh blood of the sacrificial goat that represented Jehovah. The blood represented the sins of collective Israel, and in the darkness the high priest would sprinkle the blood before the mercy seat, covering himself in the process as he interceded for his people's sins. I believe this is the context behind the imagery of robes and blood used so vividly by Book of Mormon prophets such as Jacob and King Benjamin.

Labels:

Benjamin,

Day of Atonement,

Fall Festival,

Jacob,

robe

Friday, June 4, 2010

The Annual Fall Festival in the Book of Mormon

In the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month, you shall afflict your souls, and you shall not do any work . . . For on that day he shall provide atonement for you to cleanse you from all your sins before the LORD. (Leviticus 16:29-30)

The Hebrew Bible actually records three festivals in ancient Israel during the autumnal harvest month of Tishri: New Year (Rosh ha-Shana) starting on the 1st of Tishri, the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) starting on the 10th, and Tabernacles (Sukkot) starting on the 15th (cf. Num 29 and Lev 23). However, this tri-fold division of the festival complex is generally seen as a post-exilic redaction, the consensus being that anciently there was a single yearly autumnal agrarian ingathering festival that was later divided into the three distinct feasts.[1] This is seen as happening in stages. In the time of King Josiah, the deuteronomist reformers deemphasized the land atonement and land fertility aspects of the fall festival (as well as its local nature) in order to create a national festival at the Jerusalem Temple.[2] Later, due to the exile, the solar-based harvest calendar is abandoned in favor of a Babylonian lunar system of chronology that required fixing rituals to precise calculations of new moons rather than on a fluctuating harvest season.[3] Many of the names used for months in Israel's calendar, including Tishri itself, are actually of Babylonian origin; very few of the original Hebrew names for the months are actually known, further evidence of the editing that took place due to Babylonian influence.

Labels:

Benjamin,

Day of Atonement,

Fall Festival,

Jacob

Monday, May 31, 2010

A Robe of Righteousness: From Adam to Isaiah

Let thy priests be clothed with righteousness; and let thy saints shout for joy. (Psalms 132:9)

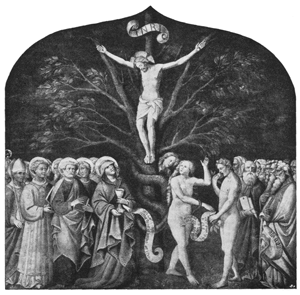

The imagery of a robe of righteousness is one of the more powerful symbols of the Atonement in the Book of Mormon. Yet it is only used twice in that text—once by Nephi and once by his brother Jacob.[1] It is a priestly symbol linked to the Day of Atonement ritual (Leviticus 16) likely influenced by Isaiah, yet at least Jacob's usage seems to also evoke imagery associated with Adam.

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Nephi and His Brothers Hit it Off

In my last post, "Psalm 1 and 2 as the Tree of Life Vision," I discussed the rod of iron in Lehi's vision and in Psalm 2 as a symbol of authority to rule both temporally and spiritually. The divine kings of the ancient Near East were given a staff at their coronation that assisted them in warding off enemies in war while shepherding their subjects along the correct path. In this respect, there is a curious event involving a rod that plays out with Nephi and his brothers.

Monday, January 4, 2010

Psalm 1 and 2 as the Tree of Life Vision

Soon after a prophetic calling that appears to include initiation into the Divine Council,[1] the prophet Lehi receives a vision of the tree of life. He describes a harrowing journey through a dark and dreary wilderness that troubles him enough that he prays for mercy. He then finds himself at the tree of life, whose fruit makes those who partake of it happy, filling them with exceeding joy. The tree is planted near a river, by which he sees a path and a rod of iron. Lehi then contrasts those who follow this path to happiness with those who choose other paths, becoming lost in midst of darkness and among the mocking throngs of those in the great and spacious building.

Labels:

psalm,

rod,

tree of life

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)